By Sarada Lahangir

A little over a decade ago, the name Jayashree Jhankar made headlines for the most basic of rights. Along with her cousins, Tribeni and Chandini, Jayashree defied centuries of tradition simply by wearing chappals and a school uniform. This act broke the taboos of their Chuktia Bhunjia community (a Particularly Vulnerable Tribal Group, or PVTG) in Sonbahali village, leading to the family’s social ostracization for years. It was a tough fight for dignity on the dusty paths of the Sunabeda Sanctuary of Nuapada District. The family never bowed down then.

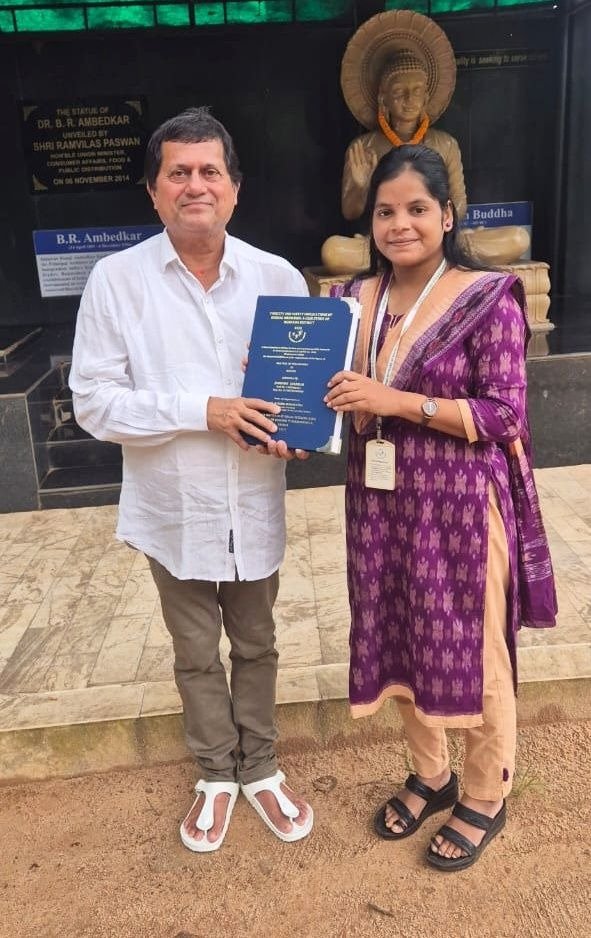

Today, that relentless fight for education has reached its zenith. Jaimini Jhankar, the sister who watched that defiance unfold, has now carved her name in history as Dr. Jaimini Jhankar, the first woman from the Chuktia Bhunjia Particularly Vulnerable Tribal Group (PVTG) to complete a PhD. Her journey from the remote, high-altitude hills (perched 3,600 feet above sea level) to the halls of KISS University is more than a personal victory; it is a powerful validation of her family’s sacrifice and a message that dreams are not limited by birth.

Dr. Jaimini Jhankar, 28, still vividly remembers those childhood days: the smell of damp earth and wild forest, the metallic squeal of her father’s worn-out bicycle, and the sheer, grinding effort of his legs pushing through ravines and streams for 10 kilometers.

“I was a child and couldn’t understand much of the meaning of ostracization,” Jaimini recalled, “but I noticed that after my cousins wore chappals and went to school, our relatives stopped coming to our house.” The experience solidified her path: “From those days, I had decided to walk in the footsteps of my sisters.”

Against the Rock of Tradition

Jaimini grew up in a community where opportunity for girls was actively suppressed. Historically, women were barred from attending school after puberty and subjected to discriminatory practices, such as not being allowed to wear petticoats, blouses, or colored sarees. Her father, Bijay Jhankar, remembered: “Our tribe has long discriminated against women… For generations, girls in the tribe were barred from attending school once they attained puberty.”

Amidst this rigid tradition, her father held a revolutionary belief. Despite having no formal education and facing local ridicule for having seven daughters, he said, “People in our community always forced us to marry our daughters after they reached puberty. But my elder daughter, Jayashree Jhankar, who was the first-generation girl to pass matriculation, taught me a lesson that girls are not less than boys. When Jayashree made headlines by wearing chappals, challenging our traditional practice, my wife and I got scared for a while because we knew our community would never accept us. But when I saw the hunger for education in the eyes of my daughter, I got ready to face any consequences.” Bijay Jhankar explained, “Our love for our daughters was greater than our fear of taboos, so we supported Jayashree. My wife too started wearing the colored saree, petticoat, and blouse, which was not allowed in our community. Now see, my daughters have proved themselves stronger than sons.”

Jaiminee’s sister, Jayashree, who was working as a teacher in an Ashram school, recalled, “Till Class Five in the local primary school, I used to wear a sari without a blouse. But then I had to switch over to the school uniform and found wearing my earlier dress very uncomfortable.” Once she broke with tradition by wearing footwear and the school uniform, senior members of her community began to threaten her parents with social boycott. “My parents were scared, but I pleaded with them, and fortunately, they agreed to support me,” she says.

Jayashree’s eyes sparkle with light as she adds, “My head is held high today because my sister Jaiminee did not succumb to tradition. She carried out our legacy to stand tall before any struggle, fighting against taboos that push women down and do not let them grow and prosper. I am a proud sister.”

A Path Forged by Kindness

Jaimini’s educational journey was a chain of monumental efforts and fortunate encounters. After finishing Class 10, the next hurdle was the 100-kilometer distance to SSD High School at Dharambandha, often requiring her to cross jungles and gorges. She confessed, “It was very hard for my father, Bijay Jhankar, to take me to the school, as my school was about 10 kilometers from my village, and we had to cross the terrains.”

The chance encounter with journalist Ajit Panda became a lifeline. “To tell you the truth, I had no idea what a graduation was,” she admitted. Panda encouraged her and paid for her admission, tuition, and hostel expenses at Khariar College. Later, Maulikrishna Sabar sir guided her through post-graduation at Balangir College.

The sacrifice was emotional, too. Living in a hostel was terrifying due to the complete lack of mobile network in her village. “I could not communicate with my family… With so much difficulty, sometimes I felt like quitting my studies halfway,” she shared. Yet, her determination to be an “example” propelled her forward.

The Ultimate Vindication and Future Legacy

Jaimini’s choice of research, ‘Toxicity And Safety Implications of Herbal Medicines: A Case Study of Nuapada District,’ was a symbolic return to her roots, using advanced science to study traditional remedies found in her home district. Her work, completed under the guidance of Dr. Rasmi Mohapatra at KISS University and Dr. Rajeev Swain, senior scientist at the Institute of Life Science (ILS), became a stunning academic milestone: no male counterpart in her tribe had ever completed a science bachelor’s degree.

Despite the victory, the weight of tradition persists. Jaimini acknowledged that because she wears footwear and eats food outside the home, she would still face post-death rituals if she were to cook in the sacred family kitchen. Yet, her focus remains resolutely on the future.

Dr. Jaimini Jhankar is now committed to teaching and mentoring the next generation, ensuring that the battles fought over chappals and bicycles will pave the way for a future where every tribal child can achieve the highest education. “My family has placed hopes on how I can help the children of our society, and I will definitely fulfill that hope.”